I went down a bit of a rabbit trail earlier today, although the subject matter has (obviously) been on my mind recently.

It started while reading the language arts series by Michael Clay Thompson. I am re-reading the Island level with Luke and including Leif this time around. We diagram sentences together daily from one or another level of practice books (we have Island, Town, and Voyage), and Levi often joins us. MCT provides wonderfully imaginative sentences to analyze, and he includes fantastic comments for each one including vocabulary and Latin stems, grammar notes, and poetic devices (alliteration, assonance, etc.).

Today’s sentence was “Yes, after the ceremony the enthusiasm was manifest.” I always write the sentence on the white board incorrectly (e.g. missing punctuation, misplaced capitals, duplicate words, or misspellings), and Leif and Luke’s most favorite task is the “mechanics check” when they are given the chance to correct all my mistakes using editor’s marks. We then identify the parts of speech, parts of the sentence, purpose, structure, and pattern. After the hard work of analysis comes the delightful reward of diagramming.

After our grammar work this morning, we moved on to start the vocabulary book, Building Language, in which the author takes us back to the history of Rome and the beauty and strength of the arch as it relates to architecture. He then compares the arch to the Latin language and how it influences our own.

The boys began to construct Playmobil worlds in the front room while I continued to read aloud from the poetics book, Music of the Hemispheres. It opens with a poem by Emily Dickinson: "How happy is the little stone/ That rambles in the road alone/ And doesn't care about careers/ And exigencies never fears..." [My oldest son piped up to tell me the definition of "exigencies" as applied to logical fallacies. As hard as this life can be many days, I was reminded why we’re on this adventure called homeschooling.]

In the preface of Music of the Hemispheres, Michael Clay Thompson writes:

“Being a poet is much like being a composer of symphonies. Just as a composer writes each note on a musical staff, and composes harmonies for the different instruments, and knows when to enhance the percussion or the woodwinds, a great poet has an array of tools and techniques at hand, and puts each sound on the page, one sound at a time, in a deliberately chosen rhythm, for a reason.”

MCT talks about poetry being the "music of the hemispheres" meaning that poetry uses both sides of the brain in a way similar to music (utilizing sounds, rhythm, precise form, and creativity).

Just a few short minutes after finishing our reading for the morning, I came across the following short, entertaining, and fascinating video (thank you, Facebook).

I started wondering if structured dance affects the brain in the same way, as it is musical and physical. A smidge more rabbit-trailing, and I came across this video (also short, fascinating, and entertaining—oh, how I love TED). Ah, of course. The nine muses of Ancient Greece: tragedy, comedy, poetry, dance, songs, history, astronomy (music of the spheres!), hymns, and epic poetry.

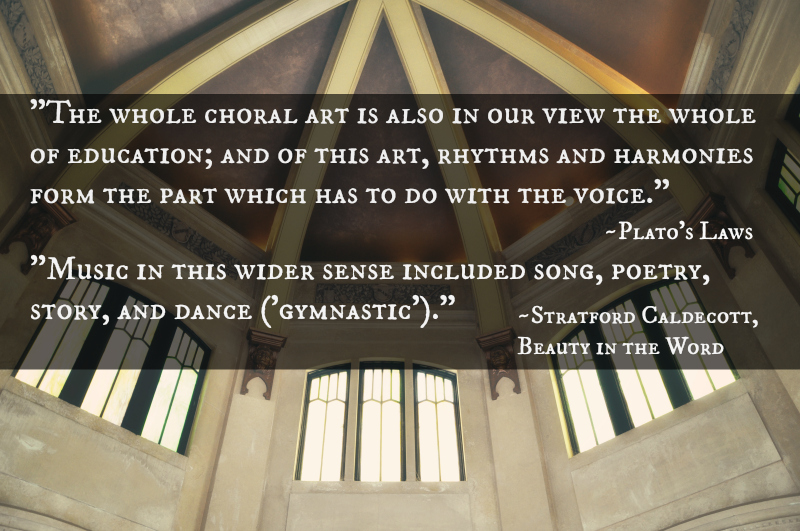

[At this point in my rambling, I’m itching to share twenty quotes about educating the poetic imagination, music, and the history of classical education from Beauty for Truth's Sake: On the Re-enchantment of Education by Stratford Caldecott, but that would make an already lengthy blog post unreasonably unwieldy. You’ll just have to read the book yourself.]

And then I began free-falling down a rabbit hole.

:: How to Read Music (engaging introductory video, again by TED). This brilliantly sums up the current music theory unit we are studying in the Classical Conversations Foundations program.

:: Reading a Poem: 20 Strategies @ The Atlantic. This is a surprisingly humorous and quite helpful how-to essay.

7. A poem cannot be paraphrased. In fact, a poem’s greatest potential lies in the opposite of paraphrase: ambiguity. Ambiguity is at the center of what is it to be a human being. We really have no idea what’s going to happen from moment to moment, but we have to act as if we do.

12. A poem can feel like a locked safe in which the combination is hidden inside. In other words, it’s okay if you don’t understand a poem. Sometimes it takes dozens of readings to come to the slightest understanding. And sometimes understanding never comes. It’s the same with being alive: Wonder and confusion mostly prevail.

:: This Bird’s Songs Share Mathematical Hallmarks With Human Music @ Smithsonian. The hermit thrush prefers to sing in harmonic series, a fundamental component of human music.

:: 50 Great Teachers: Socrates, The Ancient World's Teaching Superstar @ nprED. [Yes, this is a stretch, but we’re talking about education in Ancient Greece, right?]

"That's at the heart of the Socratic method that's come down to us from the streets of Athens: dialogue-based critical inquiry. The goal here is to focus on the text, ideas and facts — not just opinions — and to dig deeper through discussion."

"The Socratic method forces us to take a step back from that and ask questions like: What's going on here? What does this possibly mean?" Ogburn says. "What's important? What's less important? What might be motivating this person to say this?"

:: Researchers explore links between grammar, rhythm @ Vanderbilt University. [If this doesn’t bring us full circle, I don’t know what would.]

In grammar, children’s minds must sort the sounds they hear into words, phrases and sentences and the rhythm of speech helps them to do so. In music, rhythmic sequences give structure to musical phrases and help listeners figure out how to move to the beat.

And to reward you for your perseverance all the way to the end of this post:

THAT WAS AWESOME. Thanks Heidi!

ReplyDelete